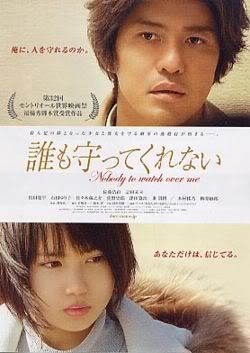

Nobody to Watch over Me

Title: Nobody to Watch over Me

Rating: 4.5/5

Genre: Drama

Language: Japanese

Starring: Kôichi Satô, Mirai Shida

Director: Ryôichi Kimizuka

Japan has been a rapidly growing interest of mine, not just in film (as you can see from my watching habits) but as a country in itself. Fiercely independent like no other country that springs to mind, proudly isolated from the western world with their own distinct brands of music, cinema, culture and ideals. It is this pride in their country, their general modest and polite attitudes and general desire to avoid controversy (the ‘extreme’ films that have become so popular overseas something of a backlash against this idea) that led me to believe that something like this would never be produced; boldly criticising the clash of cultures is never an easy thing to do, but this film has tastefully succeeding in doing just that.

If one aspect has been brought from the west, it would be the idea of free press and the media, reporters harassing and hunting for a story with little to no regard for those they follow, but when combined with the values held by many, the result quickly escalates into a situation that feels all too readily imagined. Following the sister of a young boy suspected in a double homicide, it is not just him held accountable but the media’s obsession with discovering a story that quickly results in the entire family coming under scrutiny, the press demanding a public apology before a trial can even be arranged. With only a begrudging police escort forced to protect her, he makes little show of hiding his resentment for being put on the case, having his own issues to resolve.

If one aspect has been brought from the west, it would be the idea of free press and the media, reporters harassing and hunting for a story with little to no regard for those they follow, but when combined with the values held by many, the result quickly escalates into a situation that feels all too readily imagined. Following the sister of a young boy suspected in a double homicide, it is not just him held accountable but the media’s obsession with discovering a story that quickly results in the entire family coming under scrutiny, the press demanding a public apology before a trial can even be arranged. With only a begrudging police escort forced to protect her, he makes little show of hiding his resentment for being put on the case, having his own issues to resolve.At times bordering on the absurd, the extreme lengths gone to by the media and the impact the internet has had, public message boards abusing their anonymity to disclose information as to their whereabouts, digging up dirt and stirring a media frenzy against everyone involved; whether exaggerated or not I couldn’t say, but its plausibility alone is something that is frightening. Make no mistake, this is a side of Japan you are unlikely to see anywhere else; the side where a family is made to change their names and identities and split up in order to have any hope for protection; where the suspect can be detained for days for questioning and the media throw bricks at your window just to get your attention, screaming for justice to be served and condemning all who stand in their way, willing to resort to blackmail and betrayal for five minutes of fame; where the constant accusations and media popularity forces you to become like an escaped prison convict on the run, and as we’re told from the start, many become so broken by the ordeal that they resort to suicide - the only form of apology the public are willing to accept.

Superbly performed by the two leads, it is there naturalistic approach to the proceedings that kept things grounded, the script allowing for such a depth of character detail that unquestionably assisted in their development of realistic relationships and emotions, their backgrounds readily explored through flashbacks and interactions with people from their past. The most apparent initial animosity and the constant influx of new characters somehow tied to the two protagonists serving to constantly explore additional ideas from the internet’s role in modern times to the burden of guilt carried from a simple mistake, and finding the strength to forgive them for their imperfections. The locations and soundtrack used is once again very minimal, derisively attempting to neither demean nor glorify any of the proceedings but instead leave it bare, only serving to accent the pivotal points that the director intends to make to great effect.

Superbly performed by the two leads, it is there naturalistic approach to the proceedings that kept things grounded, the script allowing for such a depth of character detail that unquestionably assisted in their development of realistic relationships and emotions, their backgrounds readily explored through flashbacks and interactions with people from their past. The most apparent initial animosity and the constant influx of new characters somehow tied to the two protagonists serving to constantly explore additional ideas from the internet’s role in modern times to the burden of guilt carried from a simple mistake, and finding the strength to forgive them for their imperfections. The locations and soundtrack used is once again very minimal, derisively attempting to neither demean nor glorify any of the proceedings but instead leave it bare, only serving to accent the pivotal points that the director intends to make to great effect.In most films the villain is always portrayed as a single entity, a person or organisation that can readily be scrutinised and become the audience’s focal point of derision and condemnation, but when that entity is an idea; a constantly shifting body made up of the few, feeding an entire society, it causes a very introspective point of view, challenging your own thoughts regarding the idea of free press and free speech. This isn’t simply a notion that feels limited to Japan but one that isn’t too far removed from attitudes in Europe and the US either and it’s surprising that it is the Japanese that are the first to bring it to the spotlight (this particular film was nominated to represent Japan in the Oscars this year). The initial notion of the torturer being one of democracies most greatly valued principles was what drew my interest but they go beyond a simple demonstration of its destructive power, proving to be one of the greatest films of this genre I’ve seen for a while.

Comments

Post a Comment